December 6, 2014

Humble Attitude in the Practice of Tai Chi

by Inge Kutt Lewis

A recent discussion with a senior student at the gwan brought up the word “humble.” The dictionary definition is (1) modest and unassuming in attitude and behavior; (2) feeling or showing respect and deference toward other people; and (3) relatively low in rank and without pretensions. What about feeling humble towards the art of Tai Chi? What does that mean? According to the senior student, it means getting out of your own way. He clarified it by saying that many students try too hard, strain to control their bodies, and force the movements. If you get out of your own way and allow the movement to dictate your body, you are going with, instead of against, the flow. In order to get out of your way, your attitude has to be humble; has to acknowledge that the art knows more than you do; has to let go of control.

Some students regard their own bodies like a fractious horse that needs taming. Actually, our bodies have their own knowledge and wisdom if we just pay attention. I should know since I always assumed my leg can only do this limited range of movements and can bear no weight. I have obviously narrowed my belief instead of broadening it. In fairness, until I started Tai Chi, nothing challenged my hard-held belief: not physical therapy, sports, or the Alexander Technique. In Tai Chi, however, feet, legs, and hips are our primary tools; the foundation on which every movement in Tai Chi is built. Nothing has prepared me for this intense focus. My first reaction was, “I certainly cannot do this.” Then I had to rethink, “What am I doing in a Tai Chi class, if my first reaction will always be, I can’t do this?” Now, my favorite saying is, “Let’s see what happens.” And that is when miracles start.

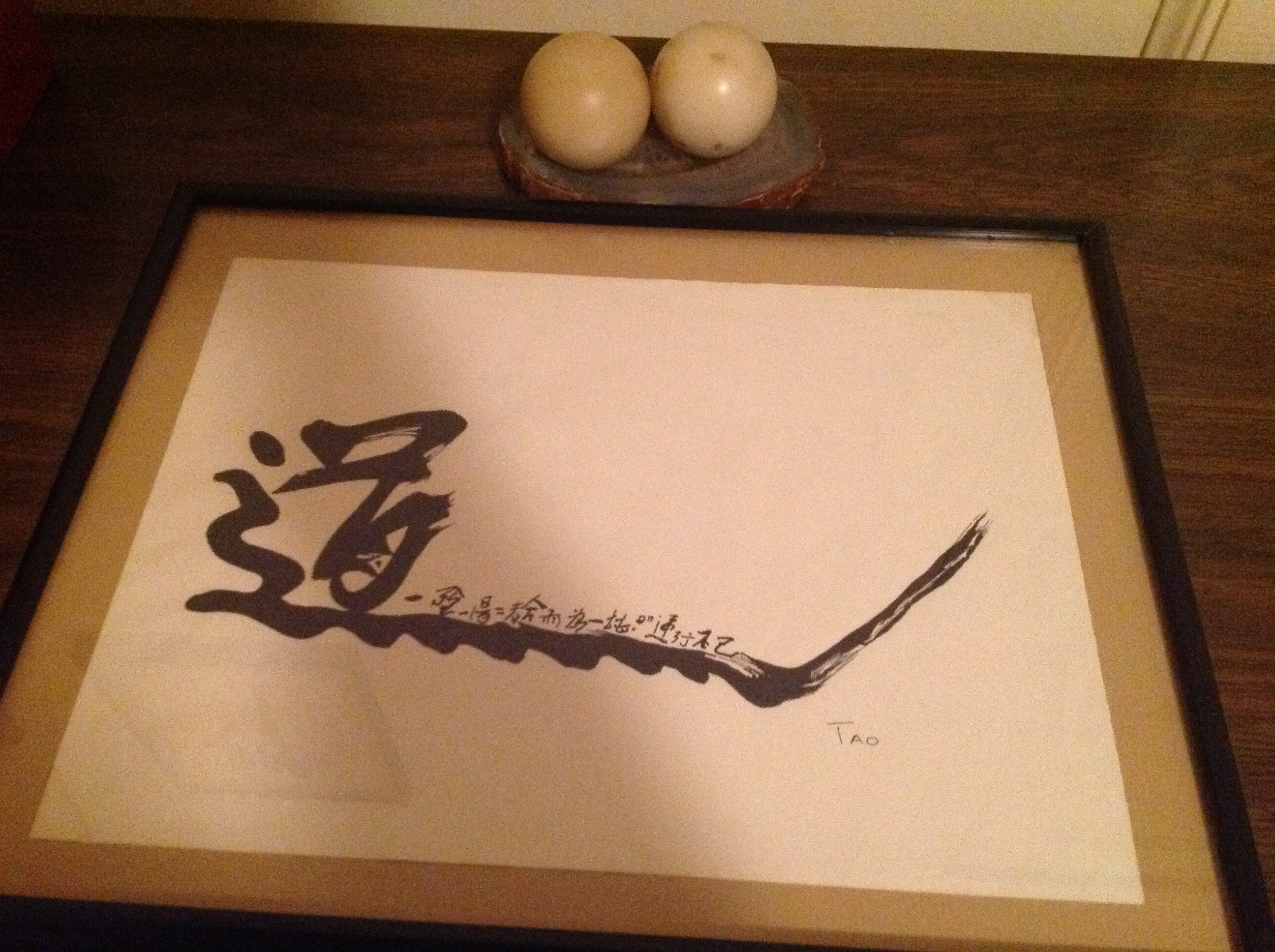

Humbleness actually permeates the gwan and the practice of Tai Chi. The first thing we do, before we enter the teaching room, is to bow. Then we bow to our lineage; we bow to Sifu; and later, we bow to his assistant. We end the class with bows as well. Bowing means we acknowledge that we are here to learn. If we do not take bowing seriously, then how can we have the right attitude to learning, i.e., admit that we are here because we know nothing? Humbleness is also a part of a respectful attitude: we respect Sifu, we respect our fellow students, and we especially respect the art. I believe, quite firmly that, without humbleness, we will never learn to flow with the Tao or the Chi because it means letting go of our self-image as being in control or all-knowing. Interestingly, paying attention to the path we are on rather than on the goal requires humbleness, too, because it’s opposite, impatience, not only leads us away from the here and now, but also indicates arrogance.

Humble attitude is also the foundation of our internal well-being: alert mind, calm heart, and contented feeling. It is an attitude that these are all we need to feel happy. Wanting more is like gluttony; if you can’t be happy with these three attributes, then you will never be happy because your concept of happiness is based on wrong assumptions. Like my friend’s daughter once cried, when her father denied her a helium balloon being sold in a park, “But it would have made me so happy.” Really?

Sometimes, being humble is really easy: Just think of stance training or static stretches. On the other hand, those two examples are also sources of great wonder and joy. The discovery that you haven’t fallen over in stance training or the fact that you can actually touch your toes in static stretches are sources of great satisfaction and awe. If we did not resist situations where our notions of ourselves are humbled, we could grow and expand our repertoire like parched plants being given water.

Humbleness is also at the basis of patience and persistence, two qualities that are vitally necessary to the practice of Tai Chi. The repetitions needed until the movements are ingrained in the body are many, but if each movement is a source of joy, then tedium falls away as if such a thought never existed.

So, as we bow to the gwan, to our lineage, to our Sifu, we also bow to the awesome experience of learning the art of Tai Chi.

I will end by quoting from The Way of Life According to Lao Tzu, translated by Witter Bynner, No. 67:

Everyone says that my way of life is the way of a simpleton.

Being largely the way of a simpleton is what makes it worth while.

If it were not the way of a simpleton

It would long ago have been worthless,

These possessions of a simpleton being the three I choose

And cherish:

To care,

To be fair,

To be humble.

When a man cares he is unafraid,

When he is fair he leaves enough for others,

When he is humble he can grow;

Whereas if, like men of today, he be bold without caring,

Self-indulgent without sharing,

Self-important without shame,

He is dead.

The invisible shield

Of caring

Is a weapon from the sky

Against being dead.